Each year, horseshoe crabs emerge from Delaware Bay under the full moon in May to mate and lay eggs, attracting large numbers of migrating shorebirds. These birds, some of which will double their weight in just a week, feed on the protein-rich eggs to fuel their long journey between South America and the Arctic. This unique ecological event, which occurs nowhere else in the world, has become a critical area for scientific research aimed at preventing future flu pandemics.

In light of the ongoing H5N1 flu outbreak affecting poultry and dairy cattle across the United States, scientists are urgently studying the birds at this location. The research, led by Dr. Pamela McKenzie and her team at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, focuses on collecting bird droppings to better understand the spread of flu viruses. Dr. Robert Webster, a New Zealand virologist, pioneered this research, linking flu viruses to birds’ digestive systems. His groundbreaking work continues to drive efforts to prevent future pandemics.

Dr. Robert Webster PC:CNN

Dr. Robert Webster, now retired but still involved in research, was astounded when he discovered that flu viruses were not replicating in the respiratory tract of birds, as previously thought, but in their intestinal tract. This led to the realization that infected birds were spreading the virus through their droppings, which would end up in the water. Bird droppings, or guano, from infected birds are teeming with flu viruses, and nearly all known flu subtypes, except for two, have been found in birds. The remaining two subtypes are found in bats.

Webster’s team first visited Delaware Bay in 1985 and discovered that 20% of the bird poop samples they collected contained influenza viruses. This finding highlighted the region as a critical location for tracking flu viruses along the Atlantic flyway, which spans from South America to the Arctic Circle. Monitoring these viruses in this area can provide early warnings of potential flu outbreaks.

The research project, which has become one of the longest-running influenza sampling initiatives, is now led by Dr. Richard Webby at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Webby, who also heads the World Health Organization’s Collaborating Center for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals, explains that predicting pandemics is like forecasting tornadoes: you need to understand normal patterns to detect changes that signal a potential outbreak.

This year, a concerning development occurred when H5N1, a highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), was detected in dairy cattle in Texas for the first time. This shift raised alarms, as H5N1 had never been known to infect cows before. H5N1, unlike low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI), causes severe illness in birds and has been devastating to poultry farms. Infected flocks are typically culled to prevent further spread and reduce suffering.

This isn’t the first time U.S. farmers have faced a highly pathogenic bird flu. In 2014, migrating birds from Europe introduced the H5N8 virus to North America, leading to the culling of more than 50 million birds, which eventually halted the outbreak. The U.S. remained free of highly pathogenic bird flu for several years. However, the same strategy has not been as effective against H5N1, which arrived in the U.S. in late 2021. Despite aggressive culling of infected poultry, H5N1 has continued to spread and has also started infecting a wider range of mammals, including cats, foxes, otters, and sea lions, bringing it closer to being able to spread easily among humans.

While H5N1 can infect humans, it hasn’t been able to spread from person to person due to differences in cell receptors between birds and humans. A recent study in Science revealed that a single genetic mutation in the virus could allow it to infect human lung cells, increasing the risk of human-to-human transmission.

The research team in Cape May had not previously detected H5N1 in their bird samples, but with the virus spreading among livestock in several states, they were concerned it may have reached the birds as well. Dr. Pamela McKenzie and her colleague Patrick Seiler carefully collected guano samples from the beach, preparing them for analysis. Over the course of the week, they gathered 800 to 1,000 samples, each of which would be sequenced to decode the virus’ genetic makeup. The results would be uploaded to an international database, aiding scientists in tracking influenza strains worldwide.

The team focused on specific bird species, such as seagulls, which have been found to carry certain viruses not seen in other birds. The samples would be sent to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis and also delivered to Dr. Lisa Kercher, who was awaiting them at an RV park nearby.

Dr. Lisa Kercher director of lab operations for St. Jude Children’s Research PC:CNN

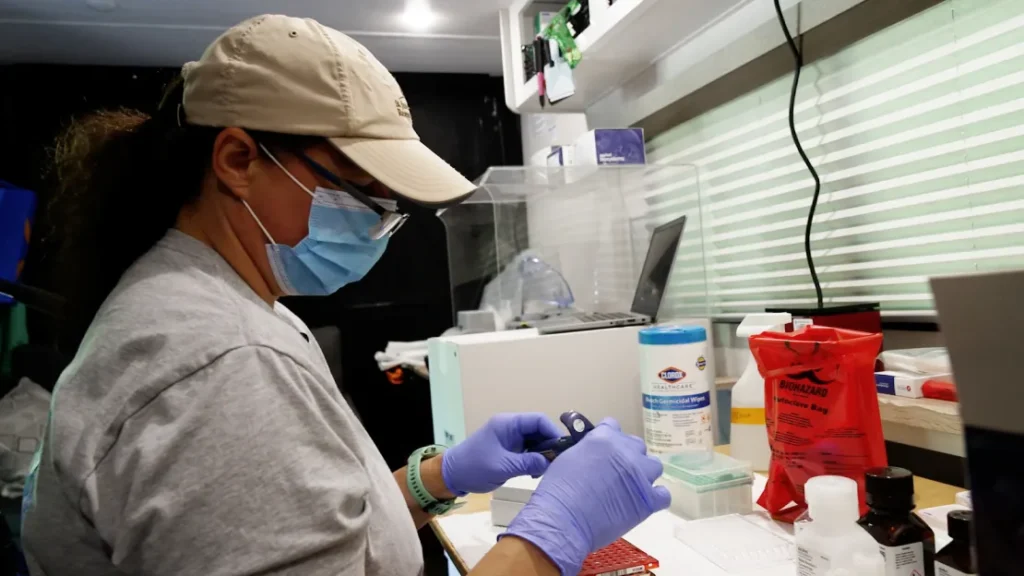

Dr. Lisa Kercher, the director of laboratory operations at St. Jude, transformed a typical RV into a mobile lab, parked among other campers, to test if it could expedite the team’s fieldwork. “We take samples in the field, send them back to the lab, and then an army of technicians works on them,” Kercher explained. However, the process can take months to identify the exact subtypes of the viruses. “If I’m here in May, I won’t know the subtypes until September or October,” she said.

Kercher’s goal is to quickly screen the samples in the field to determine whether they contain influenza viruses. Each year, about 10% of the samples collected test positive for flu viruses. By identifying the positive samples on-site, the team could send only those to the lab, speeding up the overall processing.

After fully sequencing the samples this year, the team did not find H5N1 in either the Cape May or Canadian duck samples. “We don’t know exactly why,” Kercher said. “We’ve always been curious about that.”

After finishing their work in Cape May, Dr. Lisa Kercher drove the mobile lab to northern Alberta, Canada, to test ducks that would be breeding in the area over the summer. The team has been testing ducks in Canada for 45 years, but this was the first time they used the mobile lab there. Following the Alberta trip, Kercher drove the RV to Tennessee to test ducks in their wintering grounds.

Meanwhile, the H5N1 virus continued to spread, appearing in cattle herds across the Midwest and California. There were reports of human infections, mostly mild and linked to farmworkers, but no human-to-human transmission was detected. Toward the end of summer, the outbreaks in cattle slowed, but serious human infections soon followed. A teenager in Vancouver was hospitalized with respiratory distress, and in Louisiana, a person became seriously ill after exposure to a backyard flock. The virus found in these human cases was a slightly different strain than the one circulating in cattle. While the virus in cattle is from the B3.13 genotype, the human infections were caused by the D1.1 genotype, which has been circulating in wild birds and poultry, according to the CDC.

After missing the virus in the spring and summer, the St. Jude team moved the mobile lab to northwest Tennessee, a major wintering ground for mallards and other ducks. In November and December, they swabbed 534 ducks and identified the D1.1 strain in about a dozen samples. “We did get the same strain causing problems in humans and wild birds,” Kercher said.

The D1.1 strain is a newer group of viruses, and scientists are still studying its characteristics. The team’s samples have helped link the virus to the Mississippi flyway, which runs from central Canada down through the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico. Scientists are working to determine when the strain emerged and began circulating as a distinct type. The virus seems to have evolved through reassortment, where two viruses infect the same animal and swap genes, resulting in significant genetic changes.

The team’s recent surveillance data contributed to a new preprint study, led by Dr. Louise Moncla at the University of Pennsylvania, analyzing the evolution of viruses. The study revealed that the H5N1 outbreak in North America, which began in 2021, was caused by eight separate introductions of the virus by migrating waterfowl and shorebirds along the Atlantic and Pacific flyways. Moncla’s team suggests that the current outbreak hasn’t been stopped by aggressive culling, as in 2014, because wild birds continue to introduce the virus into farmed and backyard flocks.